Collapsible content

Current

Grunts Rare Books is pleased to present Psychic States, a solo exhibition by Justin Guthrie, open December 19th, 2025 through February 1st, 2026. Psychic States features 12 new sculptures, each a small plexiglass box filled with debris collected from historic locations across Los Angeles’s cultural mythology.

Grunt's Radio: Curated by Lia Kohl

Grunts Rare Books is pleased to announce the next iteration of Grunt’s Radio, curated by Lia Kohl.

Please welcome Jeff Kolar to the radio! Jeff’s mix of four unreleased tracks will play during open hours on Saturdays and Sundays 1-4pm beginning December 20th.

Jeff Kolar is a composer, sound artist, and founder of Radius, an experimental radio broadcast platform established in 2010. His work has been exhibited internationally at The Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, Museum of Arts and Design, CTM Festival for Adventurous Music (Berlin, Germany), Tsonami Festival de Arte Sonoro (Valparaíso, Chile), Radio Revolten Radio Art Festival (Halle Saale, Germany), and reviewed in The New York Times, The Wire Magazine, Red Bull Music Academy, and more. His work has been commissioned by ORF Kunstradio (Vienna, Austria), Deutschlandradio Kultur (Berlin, Germany), Ràdio Web MACBA Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (Barcelona, Spain), and aired on independent radio stations all over the world.

GRUNTS ORIGINALS

-

Grunts Rare Books Holiday Gift Certificate

Regular price From $20.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Stephanie LaCava: Nymph (Verso, 2025)

Regular price $19.95Regular priceUnit price / per -

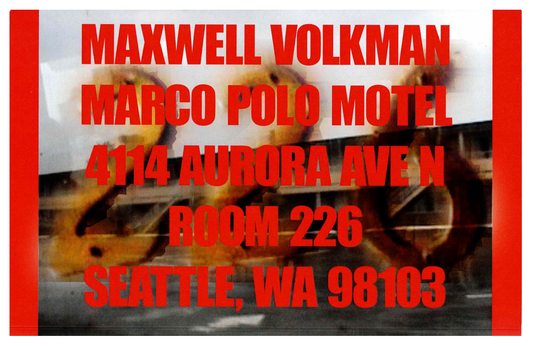

Maxwell Volkman: 226 (Grunts Rare Books, 2025)

Regular price $18.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

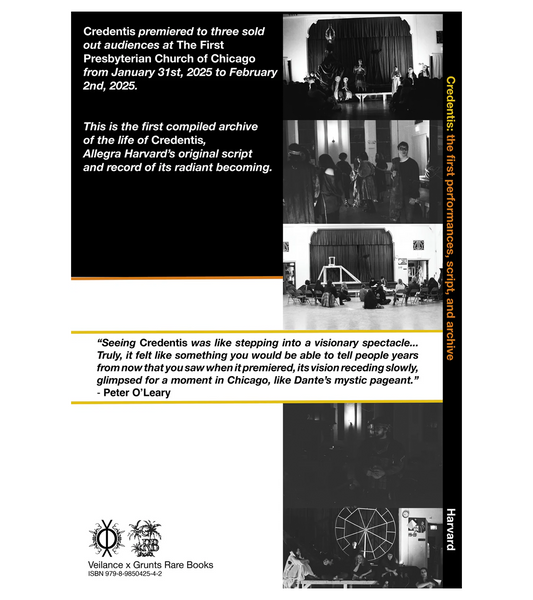

Allegra Harvard: Credentis (Grunts Rare Books & Veilance Books, 2025)

Regular price $22.00Regular priceUnit price / per